The cost and incentive structure put in place by our society for autonomous vehicle development is just as critical as an autonomous vehicle’s cost and incentive structure put in place by developers.

President Obama wrote in an op-ed in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “Right now, too many people die on our roads – 35,200 last year alone – with 94 percent of those the result of human error or choice. Automated vehicles have the potential to save tens of thousands of lives each year.” [1] Similar statements by other public officials are in agreement. These statements effectively set a goal to someday achieve zero traffic fatalities. [2]

Words like these from public officials remind us of and inspire us to work in a way that support our common goal, especially among autonomous vehicle engineers of any discipline. The code of ethics found in many engineering associations, including the NSPE, IEEE, and ASME, all refer to a similar chief canon, “Engineers, in the fulfillment of their professional duties, shall hold paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public.” [3], [4], [5]

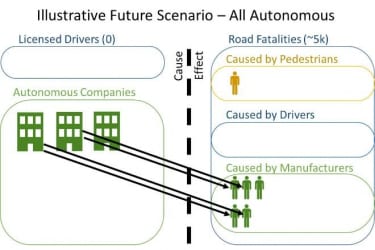

In the interest of promoting public safety, let us consider this hypothetical example. Suppose a national directive magically made a fleet of autonomous vehicles available to every driver in America and that year there were only 5,000 traffic fatalities. Given the 35,000 fatalities the year prior [6], the autonomous vehicles would be heralded as the heroes that saved 30,000 lives, and their manufacturers would claim to be “7 times safer than human drivers!”

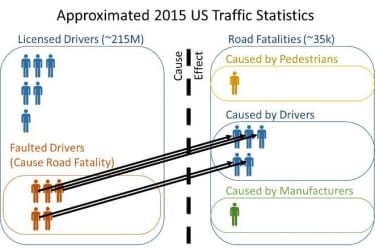

A simple illustration of the concept of tracing road fatalities back to the responsible parties in this example is shown below.

In this dream-come-true scenario, autonomous vehicle manufacturers can claim responsibility for saving 30,000 lives. Yet, they would also be deemed responsible for causing 5,000 fatalities which shifted from human drivers to autonomous vehicles.

This shift of accident responsibility, from a human driver to an autonomous computer, has been overlooked when the benefits of autonomy are counted. The advent of autonomy does not change basic facts, or liability laws. A manufacturer whose vehicles “only” cause 5,000 fatalities per year is responsible for those fatalities, no matter how much the overall fatality rate is reduced.

The oversight may be due to an inherent problem in evoking fatality rates when discussing the merits of autonomous vehicles. By evoking a rate, the context is being set that the cause of the total fatalities is random in nature, and thus normalized by a predictor. For example, we do not know all the specific causes for all the 35,092 traffic fatalities that occurred in 2015, but we do know that the amount of vehicle miles driven tends to correlate with the total number of fatalities in a given year, hence we often compare fatalities per 100 million vehicle miles traveled, or some other rate.

But what if the nature of autonomous vehicle faults are not random, or should not assumed to be random? The other type of fault we consider in functional safety is systematic, such as a failure to write code to detect traffic lights or to test for crossing pedestrians. To understand the difference between random failures and systematic failures, here is a great explanation: Random Failure vs. Systematic Failure

Systematic failures are human failures to capture the hazard, define the function, or validate performance. The potential risk can be very large for just one systematic failure. With systematic failures, the product functions as intended, but intentions should have been better. Autonomous vehicles have a high potential for systematic failures given the high amount of processing required.

In automotive functional safety, we recognize that a target of 0.0 risk is an impossible goal when it comes to random failures, but 0.0 risk is the only goal when it comes to systematic failures. This is true for window switches as well as autonomous vehicles. As engineers we make no exceptions, and neither do corporate leaders or policy makers.

To take a recent example, GM took responsibility for their ignition switch recall which, according to GM, is attributable to 124 deaths and affected 30 million vehicles. [7] There was a defect which went into production due to a human, or systematic fault, and not a random fault. In the following scenario we will see the obvious flaw in presenting these figures as rates indicative of a random fault.

We can approximate rates of the GM ignition switch fatalities with a few assumptions. We will conservatively consider the 124 deaths and 30 million affected vehicles to have been on the roads for 5 years and traveling 10,000 miles per year at an average speed of 30 MPH when driving. Expressed as rates, the number of fatalities come out to be 1 fatality per 12 billion miles or 2.5 FIT (failures in time, per 1 billion hours). We could say the ignition switch is 128 times safer than the average US driver, and 4 times safer than the strictest safety target in ISO 26262. But this certainly doesn’t mean that the failure can be considered to be OK. Misrepresentation of systematic faults as random failures is wrong at best, and misleading at worst. [8]

These simple examples may be useful to us now. This is the time when autonomous vehicle developers are setting internal targets for limiting risk due to systematic faults, and public officials are considering new policies for the public’s well being.

If policies changed to relax autonomous developers’ targets for systematic failures, nobody would be doing the developers and engineers any favors, let alone the victims. To shift so much responsibility to the engineer and to ask them to relax their standards is asking too much, especially when the engineer is, by nature, willing and able to do more for our safety. After all, they are only human, and I mean that in the best possible way.

- Barack Obama: Self-driving, yes, but also safe

- Feds set goal: No traffic deaths within 30 years

- “NSPE Code of Ethics for Engineers” – National Society of Professional Engineers, Nov 2013

- IEEE Code of Ethics – Canon 1, Oct 2006

- Code of Ethics of Engineers – ASME, Nov 2013

- FARS Data

- General Motors Ignition Switch Recalls

- Tesla – Tragic Loss

Phil magney

Great article. As a follow up I wonder how ISO 26262 will cope with AI based autonomous vehicle functions? NHSTA recently issued their highly automated vehicle policy (HAV) with hints of outcome based validation. So within the context of ISO 26262 how can AI based solutions be validated since traceability becomes hard?

Michael Woon

Thanks, Phil Magney. Sorry for the slow reply. First, I’d encourage all autonomous vehicle developers to cope with ISO 26262 sooner rather than later. The NHTSA Federal Automated Vehicles Policy states, “Manufacturers should follow standards… such as International Standards Organization…” and ISO 26262 is compatible with systems with AI or other complex algorithms. The AI validation question is an excellent question and requires more discussion than we can afford here.

ISO 26262 requires vehicle level validation by evaluating “the effectiveness of safety measures for controlling random and systematic failures” (4-9.4.3.2) key words being “systematic failures.” While ISO 26262 does not explicitly require validation through tests (“If testing is used for validation…” 4-9.4.3.1) I think we’d all agree it would be “appropriate” to apply “repeatable tests with specified test procedures, test cases, and pass/fail criteria” (4-9.4.3.5).

But I think the issue is what to test. What is a “safety measure for controlling… systematic failures” in systems with AI? If we knew what the safety measure was then vehicle-level validation testing and software-level integration testing will be more straightforward than it currently seems. If we injected systematic faults, such as corrupting the ability to detect intersections, does a safety measure detect that fault? How well? Once detected, what mitigation options are there? We’re working on a white paper which presents one concept for detecting systematic faults. While not offering 100% coverage, it may cover some percentage and help partition off smaller areas that must be analytically validated, so stay tuned.

Phil Magney

Thank you Micheal for your insights and perspective and I look forward to seeing your white paper on systematic faults. You guys do great work. Keep it up!

Mike Smiaz

Very interesting perspective. Very good point that the public will perceive a death due to an AV (i.e. Manufacturer fault) as different than one due to driver error.

Michael Woon

Thanks, Mike Smiaz. My hope is any death caused by preventable human error/neglect will not be perceived differently from a legal perspective.